Found Energy doesn't have a typical startup origin story. It started with a space robot that was supposed to eat itself. The company is currently developing the same technology to power aluminum smelters and long-distance transportation.

Almost a decade ago, Found Energy co-founder and CEO Peter Godart was a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He and several colleagues were brainstorming ways to power a probe that might visit Jupiter's moon Europa. As the team was debating the energy density of a suitable battery, an idea occurred to Godard. The aluminum used in the construction of the spacecraft held more than 10 times more energy than the most advanced batteries. Why not use spaceship parts as a power source?

“They gave me a lot of money to start a program that I affectionately called the 'Self-Cannibalistic Robot Institute,'” Godardt told TechCrunch. “We considered making it possible to use the remaining aluminum parts of the robot as fuel.”

However, as Godard continued his research, he developed a different idea. “There was a moment when I realized my time would be better spent solving the problems of the planet,” he said. His timing couldn't have been better. Although Congress cut some funding for the European mission, JPL allowed Godardt to bring his intellectual property to MIT, where he continued to work on the problem during his doctoral program.

For Godardt, aluminum had some obvious advantages. Aluminum is the most abundant metal in the earth's crust, can store twice as much energy per unit volume as diesel without being volatile, and can recover 70% of the original electrical energy used as heat . he sniffed it. “I thought, oh my god, I have to do something about this,” he said.

To release the energy contained in refined aluminum, Godardt needed to find a way to break through the metal's defenses, so to speak. “If you put a chunk of aluminum in water and tried to oxidize it using water, it would take thousands of years,” he said.

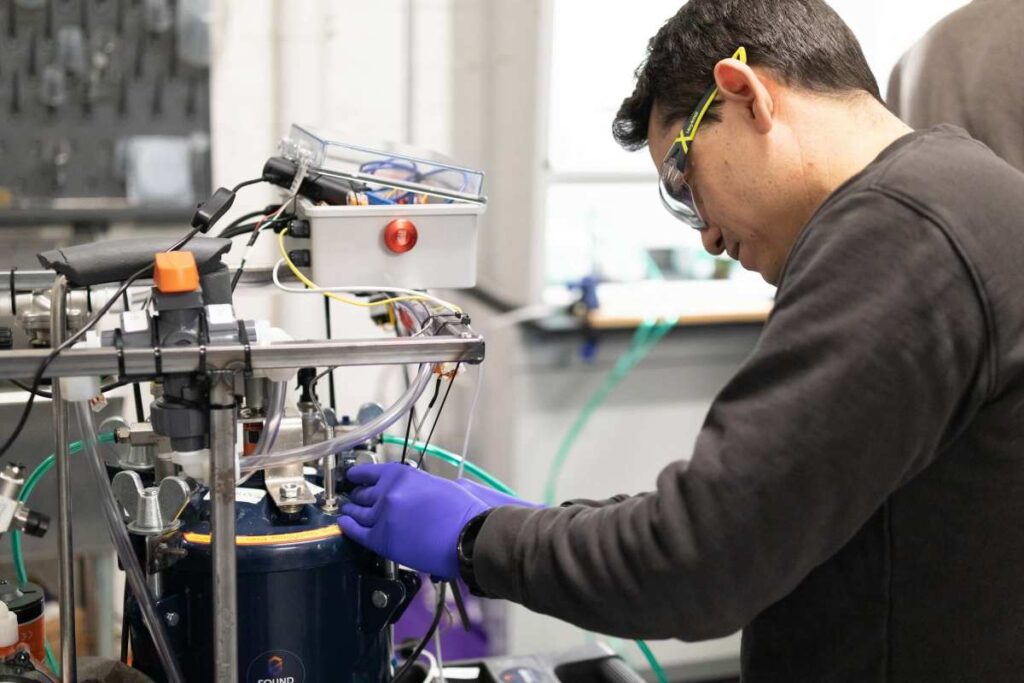

Godart's process is much faster. When you drop water onto Found Energy's catalyst-coated aluminum, the reaction releases heat and hydrogen gas, and the metal's surface immediately begins to bubble. Within seconds, the aluminum begins to expand as the hydrogen bubbles try to exfoliate it. This allows the water to penetrate further into the metal, and the process is repeated over and over again until a gray powder is left behind. “We actually call this fractal delamination,” Godardt says.

Found Energy can collect the steam and hydrogen produced and use each for a variety of industrial processes. “One of the most difficult elements to decarbonize heavy industry is heat,” Godardt said. “And now we have a very flexible way to provide heat over a very wide temperature range, from 80 degrees Celsius to 100 degrees Celsius to 1,000 degrees Celsius.” In total, about 8.6 megawatt-hours per ton of aluminum. energy can be recovered.

What's left isn't wasted either. The catalyst can be recovered and the powder is aluminum trihydrate, which can be smelted again to produce aluminum metal. Contaminants such as food waste, plastic soda can liners, and mixed alloys remain larger than aluminum trihydrate powder and can be easily filtered out.

“All of this works in our process because our catalyst just eats the aluminum and basically does nothing else,” Godardt said.

Found Energy recently raised an oversubscribed $12 million seed round, TechCrunch has learned exclusively. Investors in this round include the Autodesk Foundation, GiTV, Glenfield Partners, Good Growth Capital, J-Impact, Kompas VC, Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, and Munich Re Ventures.

If using scrap aluminum, which was Found Energy's original plan, the process would be carbon negative. While the company's go-to-market strategy is targeting industrial heating, Godardt is also eyeing applications in shipping and long-haul trucking. Aluminum is slightly heavier than diesel or bunker fuel, but its energy density could be a game-changer for these industries.

One might imagine future aluminum-powered ships dropping scrap powder into a smelter to fuel their return voyage. “If you just take a little bit of that energy and go, you've essentially come up with a new shipping fuel,” he says. “Weirdly, we're kind of reinventing the solid fuel concept.”