Sri Lanka isn't known for its startup ecosystem, but one company has been something of an outlier in the South Asian island nation for the past two decades: WSO2, an open-source enterprise software provider with customers including Samsung, Axa, and AT&T, recently agreed to be acquired by private equity giant EQT, in a deal that TechCrunch reported at the time was valued at more than $600 million (we can now confirm that the valuation was, in fact, $600 million).

The transaction, which is pending regulatory approval, will see EQT become the sole owner of WSO2 and acquire all outstanding shares, including those held by WSO2 investors and current and former WSO2 employees. 30% of proceeds will go to those employees.

This liquidity event could also generate significant wealth among those looking to start their own ventures.

“This shows that equity matters. One of the things we've been adamant about since day one is that every employee is a shareholder,” WSO2 co-founder and CEO Sanjiva Weerawarana told TechCrunch in an interview. “This is a really important but not understood concept until now, because we've never had a company that's had an exit and delivered a meaningful financial return. Seeing is believing, you know? Easier said than done.”

Thriving through war and turmoil

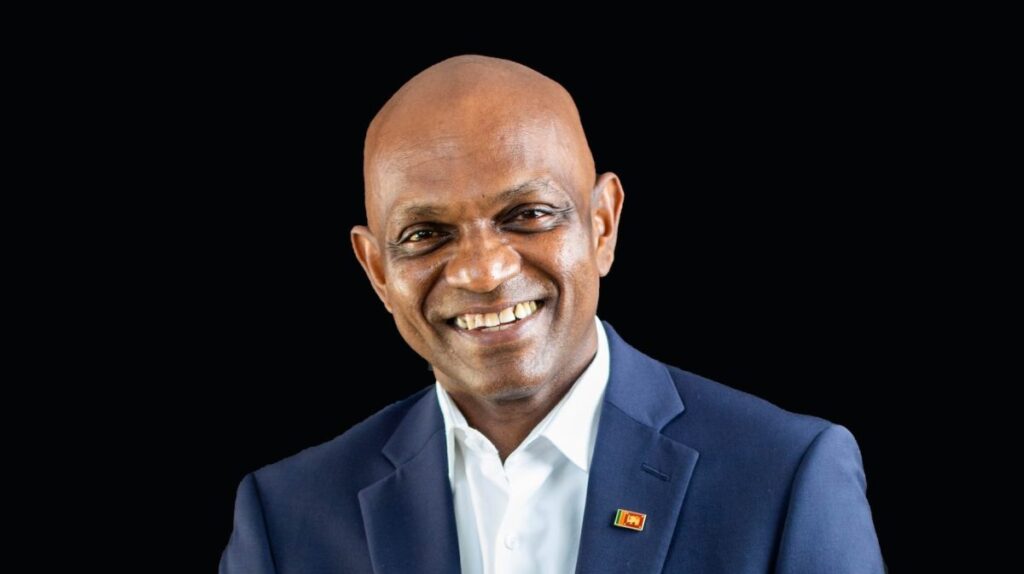

Founded in 2005 in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, WSO2 is a middleware stack that comprises tools such as API management, similar to Apigee, which Google acquired for $625 million, and identity and access management (IAM), similar to Okta, which had a $15 billion IPO price tag. Its main driving force is founding CEO Weerawarana, a computer scientist and key figure in the open source community for the past 25 years, both as a member of the Apache Software Foundation and, more recently, as the developer of Ballerina, a cloud-native, general-purpose programming language for integrating distributed systems.

Prior to WSO2, Weerawarana was part of the research and development team at IBM in the US, where he worked on developing Web services specifications such as WSDL and BPEL, and it is here that the seeds of WSO2 were sown.

“I actually tried to build a new kind of middleware stack internally at IBM, but they weren't interested,” Weerawarana says, “so I had no choice but to either start a company or give up on the idea.”

So in August 2005, Weerawarana started WSO2 with two co-founders: Davanam Srinivas, who left two years later, and Paul Freemantle, a former IBM colleague of Weerawarana's who served as CTO until he left in 2015. (Fremantle has since returned, then left again, but remains an advisor.)

Notably, WSO2's centre of gravity remains in Sri Lanka, despite years of civil war and outside pressure to relocate to the US, where Weerawarana lived for 16 years.

“I came back [to Sri Lanka] “In 2001, two weeks before I landed in Colombo, the airport was attacked by terrorists and there were still remains of the plane on the ground,” he said. “In 2005, the war was still going on. Sri Lanka as a country has not been a consistent source of peace for us, but that's OK.”

Currently, 80% of WSO2’s 780 employees are in Sri Lanka, with the remainder spread across several locations in the US, Europe and Asia.

“We wanted to show that you could build a product-driven technology company out of Sri Lanka,” Weerawarana continued. “Nothing like this had ever existed before, and there were no companies like this in India at the time. Indian companies are very service-driven, just like Sri Lankan companies. But one of the big price factors is [for staying in Sri Lanka] In almost every funding round, most investors asked me when I was going to get back. [to the U.S.]And my answer was always the same: “I'm not going back.”

It wasn't just investors who pressured WSO2 to relocate. Customers and competitors also worked against WSO2 in various ways because of its location.

“Some of our competitors have been competing with us by saying, 'Do you know where they are located?', and that's been a problem,” Weerawarana said. “And then some customers are saying, 'Why are you charging us these prices when you're based so far away?'”

On the other hand, WSO2’s geography relied heavily on the fact that it was a product-based business in a sea of services, giving it an advantage in being picky about technical talent.

“We have never had a shortage of engineering and technical talent. Over the last 19 years, we have been able to employ the best talent in Sri Lanka,” says Weerawarana. “If you are a creative engineer, would you rather work for a services company or a job where you have creative work and work with cutting edge technology?”

WSO2 CEO Sanjiva Weerawarana speaks to the media during the product launch in Colombo on February 26, 2014. Image credit: Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP via Getty Images

WSO2 CEO Sanjiva Weerawarana speaks to the media during the product launch in Colombo on February 26, 2014. Image credit: Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP via Getty Images

Intel is in

After WSO2 raised a small amount of funding from angel investors in 2005, Intel's VC arm emerged as its first backer, investing in 2006 and then several follow-on rounds.

The initial $2 million cash infusion from Intel Capital was crucial to WSO2's early growth, and well-timed. At the time, Pradeep Tagare was a senior investment manager at Intel Capital, who met Weerawarana through their connections with the Apache Software Foundation. Tagare wanted to invest in open source startups to complement two other open source investments the firm had made: Java-centric application server company JBoss (later acquired by Red Hat for $350 million) and database company MySQL (later acquired by Sun for $1 billion).

“We were looking at a series of open source investments as part of a strategic initiative with Intel, essentially building an alternative stack on Intel hardware,” Tagare explained to TechCrunch. “We had invested in JBoss, we had invested in MySQL, so we were looking for an open source middleware company, and WSO2 really fit the bill.”

Tagare's argument was that Asian countries would not only benefit from the open source movement, but also contribute greatly to it: open source software development is naturally decentralized, opening up the coding and collaboration process to people who don't work for the big tech companies of the time.

“Now they can contribute. Before, everything was controlled by the Microsofts and the Oracles of the world,” Tagare said. “Location wasn't necessarily a requirement, but being based in Asia makes WSO2 more interesting.”

A lot has changed in the 20 years since WSO2 first came out. The rise of cloud computing and microservices (software built from smaller, loosely connected components that can be developed and maintained independently, and conveniently rely on APIs) has positioned WSO2 well to help enterprises move away from traditional monolithic applications.

The AI revolution is in full swing, and WSO2 is well-positioned to capitalize on it as APIs and IAM are key components of the AI stack, from integration to authentication. Additionally, WSO2 is integrating AI into its products, and recently announced a new API manager that allows developers to integrate AI-powered chatbots into their APIs and test them using natural language, even if they can't code.

WSO2 has raised $133 million since it was founded, according to Crunchbase data, but Weerawarana clarified that only $70 million has been in primary capital: Other rounds have been made up of equity and debt, including a $93 million Series E round two years ago led by Goldman Sachs.

But no matter how the funding is broken down, there's no ignoring the fact that WSO2 was a startup dinosaur when EQT came calling: Most successful venture-backed companies exit within a decade.

So what's going on?

“Over the years there have been a number of people who have wanted to acquire us but I have resisted because I always wanted to build a company that could achieve an IPO – an independent business,” Weerawarana said.

That all changed in May, when WSO2 accepted a takeover bid from EQT Private Capital Asia (formerly Baring Private Equity Asia), the private equity firm that EQT acquired for more than $7 billion in 2022. The difference this time was simple: One of WSO2's controlling shareholders “wanted to get liquidity,” according to Weerawarana.

“They held more than 50% so this was a control deal,” he said.

The shareholder is San Francisco-based Tova Capital, a venture capital firm founded in 2012 after Vinnie Smith sold Quest Software to Dell for more than $2 billion. Quest had previously invested in WSO2, and its stake went to Dell through an acquisition, but Tova bought it back from Dell and went on to make further investments in WSO2, including buying Intel Capital's stake. Tova Capital partner Tyler Jewell also succeeded Weerawarana as CEO for two years, before Weerawarana took over as CEO again in 2020.

Weerawarana said the company has been cash flow positive since 2017 and profitable “since about 2018,” but it didn't have the luxury of having a large pool of capital to consider a “multi-year strategy,” something that would be possible under EQT, one of the world's largest private equity firms.

In fact, WSO2 said it will reach $100 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR) by the third quarter of this year, which is one of the main reasons EQT came forward.

“WSO2 has all the elements you want in a software business,” Hari Gopalakrishnan, partner and co-head of global services at EQT, told TechCrunch. “Deep, long-term relationships with enterprise clients, successful product-led growth, a technically robust product, and prudent financial management. Pick one strength, and WSO2 probably has it.”

From an outsider's perspective, selling to private equity might not seem like a dream outcome for founders who want to go public and value their company's independence, but Weerawarana argues that this outcome makes a listing more achievable.

“I started the company to build something that would last, and one of the reasons I didn't sell before is because I knew if I sold it, it would be over,” he said. “EQT doesn't have other businesses in the space and they're looking to build around WSO2, not integrate it with something else. Their goal is to build the company for five years, which is in line with my aspirations and gives us five years before an IPO.”

Driving force

Uber logo on top of the car Image credit: Marek Antoni Iwanczuk/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Uber logo on top of the car Image credit: Marek Antoni Iwanczuk/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

While running WSO2 is a time-consuming endeavor in itself, Weerawarana keeps himself busy with other endeavors, including a charity he set up in 2022 called the Avinya Foundation to help economically disadvantaged children through vocational education programs.

But in 2017, Weerawarana also began driving for Uber, a move he says is to make taking on such work more socially acceptable in Sri Lanka: if a successful businessman like him can do it, then anyone can.

“I was just picking up someone on my way home from work,” he says. “The point I wanted to make is that people who drive are no different to people who do any other job. They're providing a service, and you're paying for it. We have this idea that people who do certain kinds of jobs are not the same as other kinds of people, and it's really important to break that. Being an Uber driver is part of that. The Avinya Foundation is also focused on that issue, and we try to support all skilled workers, like artisans.”

The pandemic and other global events have temporarily halted Weerawarana's Uber career, as people rely on him to survive and he didn't want to take money from those in need.

“I would do it again. Things are getting much better,” he said. “Tourism is pretty much back to normal and there will be demand, so it might make sense for me to drive. But I don't want to take work away from other people.”