When is $14 billion in funding not enough? For a battery startup.

Northvolt, which is seeking to create a European rival to Asia's battery giants, said on Monday it was halting construction of a factory expansion and laying off 1,600 employees, about 20 percent of its workforce.

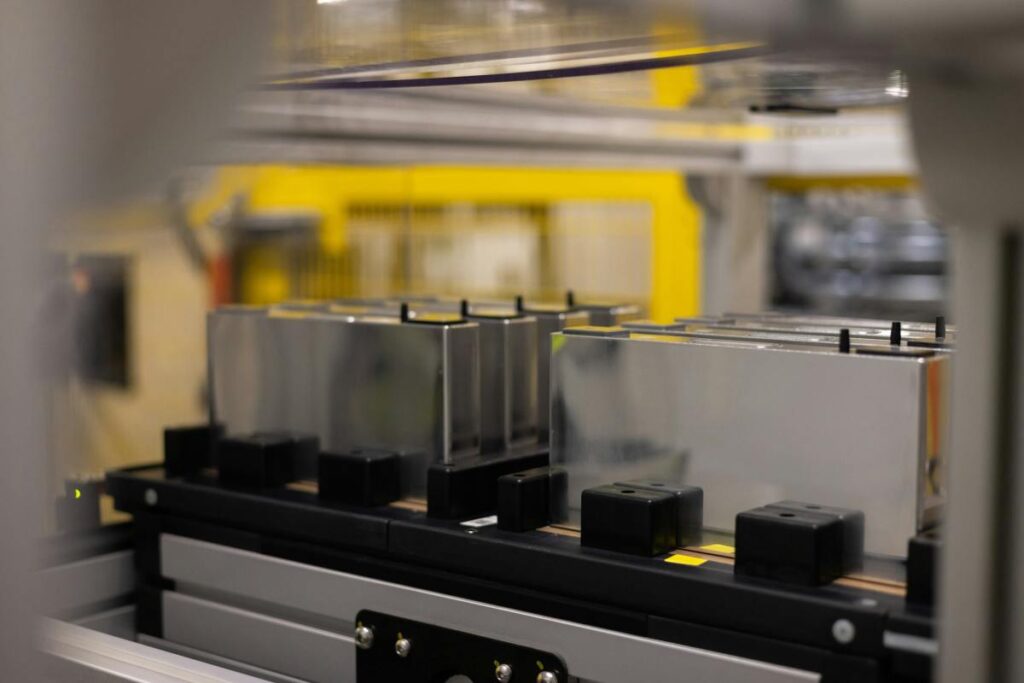

The company had planned to expand its Ett plant in northern Sweden, boosting annual production to 30 gigawatt hours. The expansion would have supplied cathode active material (CAM), a key component needed to make finished cells. The company also closed another CAM production site in Sweden on September 9. Without those plants, Northvolt would have to source from elsewhere, possibly overseas.

Northvolt said the cost-cutting was due to slower-than-expected demand growth amid automakers lowering their electric vehicle production forecasts. Execution issues may also be to blame: In June, the company failed to fulfill an order from BMW on time, leading the German automaker to cancel a €2 billion contract. Northvolt did not immediately respond to TechCrunch's request for comment, but it's unlikely that this didn't impact the company's cost-cutting measures.

Ultimately, Northvolt faces two challenges.

First, any battery startup faces huge execution risks. Batteries look simple from the outside, but the chemistry inside is incredibly complex. Developing materials that can store energy densely and safely, charge at increasingly fast rates, and last in a car for a decade or more is no easy feat. Mass production only complicates the challenge; just ask GM or LG what happens if things go wrong.

Northvolt still has hurdles to overcome. The company is essentially replicating the mature, large-scale battery manufacturing sectors that Asian countries like China and South Korea already have. Both have been at this for decades and have consistently received government support along the way. By comparison, Northvolt is only eight years old and has only recently received significant backing from the EU and other governments.

In the United States, A123 Systems tried something similar about 20 years ago. The startup pioneered the production of lithium iron phosphate batteries, which have less energy storage than other chemistries but are more durable and safer to charge. The company started by selling to power tool makers, and then, by the late 2000s, began courting automakers, who expected to buy enough batteries to support large-scale domestic production.

A123 was a contender to make battery packs for the Chevrolet Volt, but lost out to LG, and its only customer was Fisker's first model, which also made plug-in hybrids. After one of its cars caught fire during testing by Consumer Reports, A123's fate was all but sealed.

These high-profile failures don't reveal the other obstacles A123 faced, most of which had to do with setting up a battery supply chain where none yet existed. Northvolt has been a bit more successful, in part because there was political will to make it happen, but the Swedish company's announcement that it would cut back on CAM production shows that it's still not going to be easy.

The second challenge Northvolt faces is that its key automakers have yet to decide on a position on EVs. After years of advocating a move to an all-EV lineup, they have since backtracked on their most aggressive goals. Early projections from most automakers have proven to be overoptimistic, likely underestimating the amount of investment needed to produce successful products. Facing weaker-than-expected tailwinds, automakers are focusing on developing hybrids and plug-in hybrids that require far fewer batteries.

To succeed in the early market, all players need to be confident: automakers, parts manufacturers, and investors need to be confident in the future of EVs. If any one of them veers away, everyone loses. Northvolt is feeling the pain now.

Does this mean the end of battery manufacturing in Europe and North America, where Northvolt plans to expand? Not really. EV demand remains strong and growing. And because batteries are heavy and expensive to transport, it makes sense to produce them closer to EV factories. Strong incentives from the Anti-Inflation Act and the European Green Deal further help the situation. That doesn't mean Northvolt is letting its guard down; it just needs to prove it's viable. But by the time that's worked out, the market is likely ready to accept it.