Sound reveals a lot about water and where it's going.

With every washing machine cycle, dish wash, and toilet flush, water rushes into the pipes of homes, apartments, and commercial buildings, carrying waste away at breakneck speed. The whistling and buzzing sounds that water makes on its way down may seem unnoticeable. However, they are part of a unique sound signature and, with the right algorithms and hardware, can be detected and classified for preventive maintenance purposes.

What is called acoustic detection is not new science. Water departments and utilities have been using acoustic sensors for years to check for signs of leaks and wear and tear. But over the past decade or so, a group of startups has put an interesting spin on the old technology, applying acoustic water detection in new ways and places.

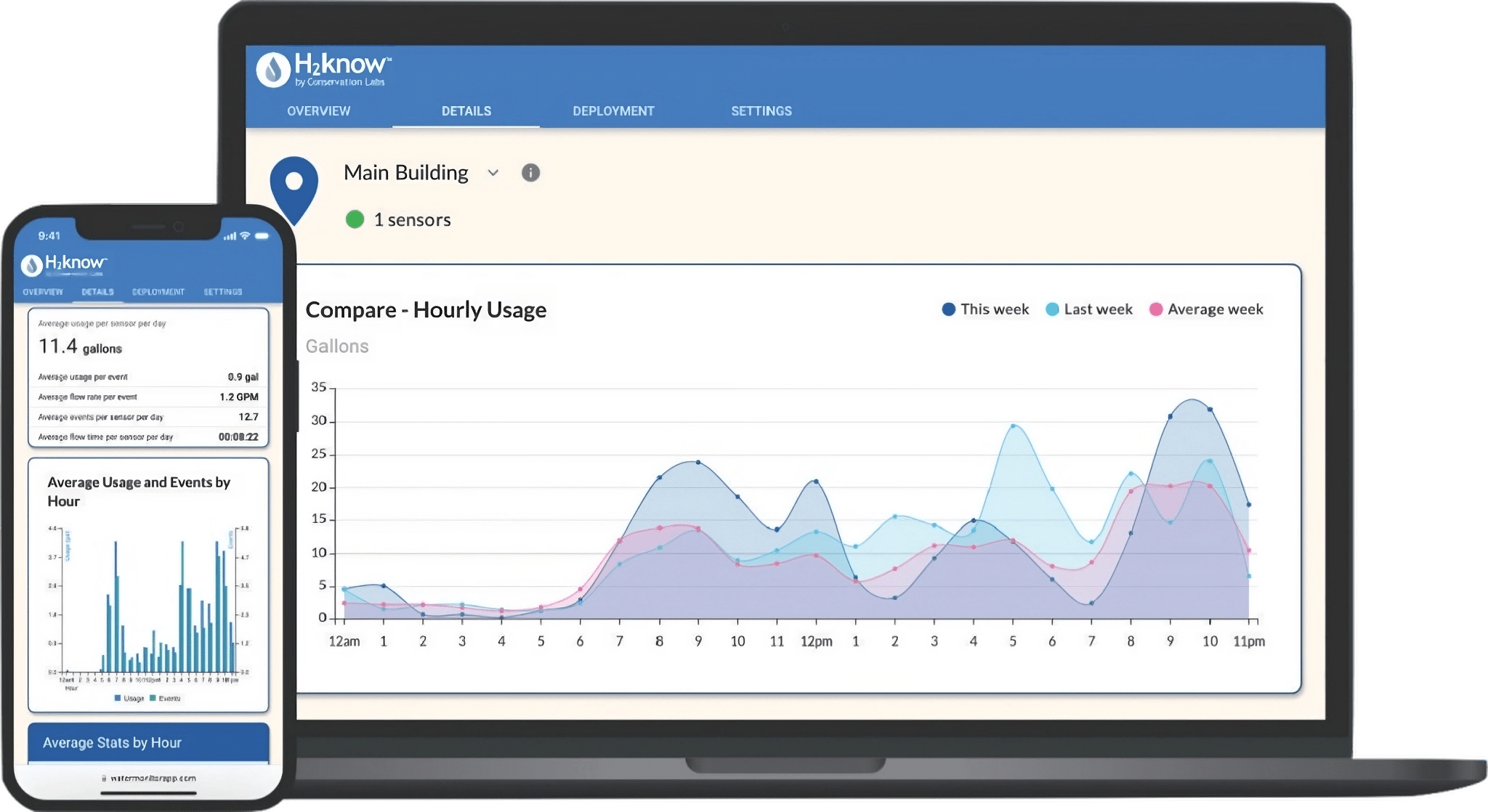

One of these startups, Conservation Labs, develops water-listening sensors that attach to pipes in homes, apartment complexes, and office premises. The sensor leverages algorithms trained in hydroacoustics to translate sound from pipes into usage statistics, leak warnings, and even maintenance recommendations.

“Sensors monitor individual units or entire buildings and provide remote visibility,” Mark Kovscek, founder and CEO of Conservation Labs, told TechCrunch in an email interview. . “There are some indirect competitors that help identify leaks and monitor the consumption of an entire building. However, Conservation Labs’ technology detects leaks in any building or pipe and monitors water usage. It is differentiated in that it monitors

Kovczek, who earned degrees in applied mathematics and industrial management from Carnegie Mellon University, was inspired to start Conservation after suffering several severe home leaks.

Conservation Labs' acoustic-based water monitor. Image credits: Conservation Research Institute

“later [leaks]”We looked for products that could monitor leaks and other water usage, but we couldn't find any that would add value,” Kovcheck said. “We realized that sound waves could indicate what was happening inside the pipe, so we developed a prototype and filed a patent in 2016.”

Currently, Conservation Labs (which earlier this month raised $7.5 million in a Series A funding round led by RET Ventures' Housing Impact Fund with participation from Sustain VC) has launched a subscription service for sensor and cloud-based monitoring services. are on sale. The sensor retails for $129, but the subscription fee is $36 per sensor per year.

Kovscek claims that after installing the sensors, conservation users typically see a 20% reduction in water usage.But like many (if not most) AI and algorithm-driven products on the market, it's hard to know. that's right How well does Conservation Labs' technology perform without extensive testing first?

Acoustic monitoring involves many variables, such as the amount of water being monitored and the material of the pipes, all of which can affect sensor readings. Depending on the sounds and numbers Conservation uses to train the algorithm, unintended biases can creep in and skew the measurements.

Kovshek claimed that Conservation takes a “rigorous” approach to developing, testing and validating its algorithms, and that the platform's accuracy is continually improving.

“A general acoustic model is created using thousands of hours of data, and then sensor-specific models are generated based on the sensor’s unique environment and the unique audio profile of what is being monitored,” he added. I did. “As the platform matures and new use cases are added, it will become more intelligent, faster, and even more extensible to new use cases.”

In any case, Conservation appears to have carved out a niche market, with annual recurring revenue reaching “seven digits” in 2023 and a customer base of around 150 companies. To avoid putting all its eggs in one basket, the startup recently launched a new acoustic sensor that monitors not only water but also industrial machinery for signs of damage or other related problems. I launched the line.

Similar to sensors that listen to water, acoustic sensors that monitor machinery are an established technology.

Image credits: Conservation Research Institute

Beyond Conservation Labs, startups like Noiseless Acoustics and OneWatt are using AI-powered sensors to better understand patterns in industrial equipment. Other companies, including Conservation, are experimenting with applying them to identify leaks in gas and oil pipelines.

“Conservation's platform not only identifies whether a machine is failing, but also the cause of the failure (e.g., is it the motor belt, is it the motor bearing, is the machine out of balance, etc.)? We can,” Kovczek said. “All this is accomplished with a single sensor using a low-cost microphone.”

Again, think about how you respond to these claims. This writer hasn't had a chance to test them, and never will.

Armed with a total of $9.5 million in venture capital, Conservation plans to release its second generation of water monitoring sensors, expand the reach and scale of its AI platform, and expand its ongoing sales and marketing efforts. To accomplish all of this, the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based company plans to hire eight of his employees and grow his team of 22 to his 30 by the end of the year.

“When it comes to sustainability, we need to focus on driving more efficient operations, federal funding for climate change and energy investments, regulations that encourage water and energy oversight, increasing water rates, and spending more on green brands. There are a lot of tailwinds, including interest from investors,” Kovcheck said. “We are focused on looking to the future, and this Series A proves the resilience of our services regardless of what is happening in the broader market.”