Earlier this month, Adrian Holovaty, founder of Soundlice, a music teaching platform, solved the mystery that had been worrisome for several weeks. The strange images, which were obviously ChatGpt sessions, continued to be uploaded to the site.

Once he solved it, he realized that ChatGpt had become one of his company's biggest hype men, but it was lying to people about what his app could do.

Holovaty is best known as one of the creators of the open source Django project, a popular Python web development framework (although he retired from managing the project in 2014). In 2012 he launched Soundslice. He tells TechCrunch that this will remain “proudly bootstrap.” Currently, he focuses on his music career as an artist and founder.

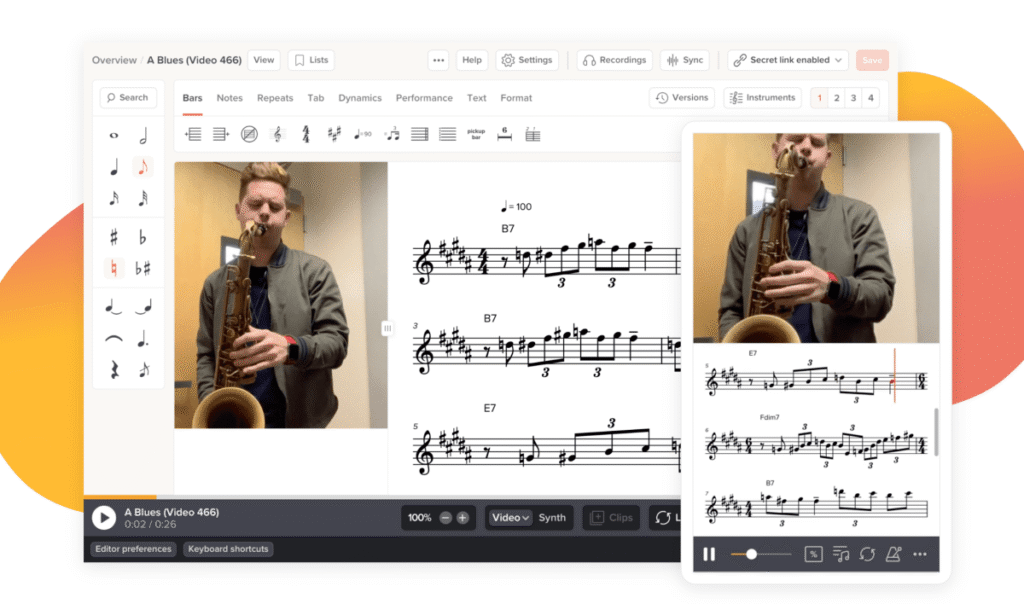

Soundslice is an app for teaching music for students and teachers to use. This is known for video players synchronized with music notation, which guides users on how to play notes.

It also offers a feature called “Score Scanner,” which allows users to upload images of paper sheet music, and uses AI to automatically turn it into an interactive sheet with notation.

Holovaty carefully looks at the error log for this feature to see where the issue occurs and where to add improvements.

That's where he started watching the ChatGpt sessions he uploaded.

They had created a lot of error logs. Instead of sheet music images, these were images of words, boxes of symbols known as the ASCII tablature. This is a basic text-based system used for guitar notation using regular keyboards. (For example, standard QWERTY keyboards do not have high-pitched keys.)

Image credit: Adrian Holovaty

Image credit: Adrian Holovaty

The volume of images for these ChatGPT sessions wasn't too troublesome, so his company's money was expensive to store them and crush the app's bandwidth, Holovaty said. He was confused and wrote in a blog post about the situation.

“Our scanning system was not intended to support this style of notation. Why were we bombarded with so many ASCII tab ChatGPT screenshots? I was mysed for several weeks.

That's how he saw ChatGpt telling people that he can hear this music by opening a Soundslice account and uploading images from a chat session. But they couldn't. Uploading these images does not convert the ASCII tab into an audio note.

He was struck by a new problem. “The main cost was reputation. New Soundslice users were going with false expectations. They were confident that they would do something we wouldn't actually do,” he explained to TechCrunch.

He and his team discussed their options: slap the disclaimer site-wide about it – “No, you can't turn chat Gpt sessions into music that you can listen to” – or he built that functionality into a scanner, despite never thinking about supporting that off-beat music notation system.

He chose to build the feature.

“My feelings about this are at odds. I'm happy to add tools to help people. But our hands feel like they've been forced in strange ways. Should we develop features in response to misinformation?” he wrote.

He also wondered whether this was the first documented case of having to develop a feature, as ChatGpt kept repeating hallucinations about it in many people.

fellow programmers in Hacker News had an interesting view on it. Some of them said it's no different to avid human salespeople who promised the world to prospects and forced developers to provide new features.

“I think that's a very appropriate and interesting comparison!” Holobaty agreed.