The victim's phone flashes with an incoming call. It may only last a few seconds, but it can end with the victim giving cybercriminals a code that allows them to take over their online accounts and exfiltrate their cryptocurrencies and digital wallets.

“This is the PayPal Security Team. We have detected unusual activity on your account and are calling you as a precaution,” the caller's robotic voice says. “Enter her 6-digit security code sent to your mobile device.”

Unaware of the caller's malicious intentions, the victim enters the six-digit code they just received in a text message into the phone's keypad.

“We got that Boomer!” a message appears on the attacker's console.

In some cases, attackers may also send phishing emails with the goal of obtaining the victim's password. But often, all an attacker needs to break into a victim's online accounts is a code from a mobile phone. By the time the victim ends the call, the attacker has already used that code to log into the victim's account as if they were the rightful owner.

Since mid-2023, an eavesdropping operation called Estate has enabled hundreds of members to make thousands of automated calls to trick victims into entering one-time passcodes, according to a TechCrunch investigation. It turned out that Estates can help attackers defeat security features such as multi-factor authentication. Multi-factor authentication relies on a one-time passcode sent to a person's phone or email, or generated from their device using an authenticator app. Once a one-time passcode is stolen, the attacker could be granted access to the victim's bank accounts, credit cards, cryptocurrency and digital wallets, and online services. Most of the victims were in the United States.

However, a bug in Estate's code exposed the site's unencrypted backend database. The Estate's database contains a line-by-line log of each attack since the site's inception, including details about the site's founders and their members, and the phone numbers of victims targeted by which members and when.

Vangelis Stykas, security researcher and chief technology officer at Atropos.ai, provided the Estate database to TechCrunch for analysis.

The backend database provides valuable insight into how one-time passcode interception operations work. Services like Estate advertise their services under the guise of providing an ostensibly legitimate service to help security professionals stress test their resistance to social engineering attacks; It falls into a legal gray area because it allows its members to use the service for malicious cyberattacks. Authorities have previously charged operators of similar sites specializing in automated cyberattacks with providing services to criminals.

The database includes logs of more than 93,000 attacks since Estate launched last year, including Amazon, Bank of America, CapitalOne, Chase, Coinbase, Instagram, Mastercard, PayPal, Venmo, Yahoo (TechCrunch) and more. It targets victims with accounts such as others.

Some of the attacks also show an attempt to hijack phone numbers by performing SIM swap attacks, with one campaign simply titled “Get a SIM swapped buddy”, which targets victims. are threatening people.

Estate's founder is a Danish programmer in his early 20s who told TechCrunch in an email last week, “I am no longer running the site.” Despite the founder's attempts to hide the estate's online operations, he misconfigured the estate's servers, revealing its true location in a data center in the Netherlands.

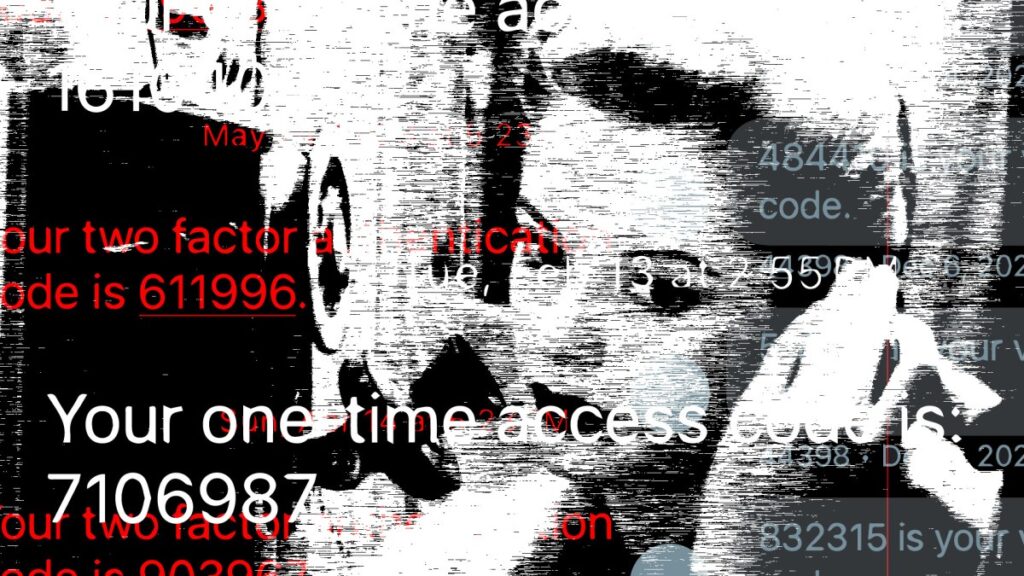

The attacker's console in the estate. Image credit: TechCrunch (Screenshot)Image credit: TechCrunch

The attacker's console in the estate. Image credit: TechCrunch (Screenshot)Image credit: TechCrunch

Estate touts itself as being able to “create a customized OTP solution that perfectly matches your needs” and explains that “our custom scripting options give you control.” Members of the estate infiltrate global telephone networks and gain access to upstream communications providers by posing as legitimate users. One of the providers is Telnyx, whose CEO David Casem told TechCrunch that the company has blocked Estate's account and an investigation is underway.

Although the estate is careful not to outwardly use explicit language that could incite or encourage malicious cyber-attacks, the database shows that the estate is used almost exclusively for criminal purposes.

“These types of services are the backbone of the criminal economy,” said Alison Nixon, principal investigator at Unit 221B, a cybersecurity firm known for researching cybercrime groups. “It streamlines time-consuming tasks. This generally means more people are subject to fraud and extortion than before these types of services existed. They lose retirement benefits due to crime. The number of elderly people is increasing.”

The estate tried to keep a low profile by hiding its website from search engines and acquiring new members through word of mouth. According to the company's website, new members can only sign into the Estate using referral codes from existing members, so user numbers are low to avoid detection by the upstream communications providers the Estate relies on. It's suppressed.

Once through the door, the estate provides members with tools to look up passwords for a potential victim's previously compromised accounts, making it the only obstacle to hijacking the target's account. is only a one-time code. The estate's tools also allow members to use custom-made scripts containing instructions to trick targets into handing over one-time passcodes.

Some attack scripts are designed to verify stolen credit card numbers by tricking victims into submitting the security code on the back of their payment cards.

According to the database, one of the estate's largest telephone campaigns targeted older victims on the assumption that “baby boomers” were more likely to receive unsolicited calls than younger generations. Ta. The campaign received approximately 1,000 calls and relied on a script that notified cybercriminals of each attack attempt.

“The old woman answered!” will flash on the console when the victim answers the phone, and “Life support unplugged” will be displayed if the attack is successful.

The database shows that the estate's founders are aware that most of their customers are criminals, and the estate has long promised privacy to its members.

“We do not log any data and do not require any personal information to use our services,” the estate's website states, adding that upstream communications providers and tech companies typically They neglect requiring customers to verify their identity before connecting them to their network.

But that's not strictly true. The estate has kept detailed records of all attacks carried out by its members since the site's launch in mid-2023. The site's founder also maintains access to the server's logs, which include all calls made by members and when members load pages on the estate's website at any time on the estate's servers. I could see what was happening in real time.

The estate also tracks prospective members' email addresses, according to the database. One such user's girlfriend said she wanted to join Estate because she had recently “started buying CCS” and believed Estate was more reliable than buying a bot from an unknown seller. I said that. Records show the user was later approved to become an estate member.

The published database shows that some members relied on the estate's promise of anonymity and left snippets of personally identifiable information, such as email addresses and online handles, in the scripts they wrote and the attacks they carried out. is shown.

The estate's database also contains member attack scripts that allow attackers to exploit weaknesses in the way major technology companies and banks implement security features such as one-time passcodes to verify a customer's identity. A specific method for exploiting this information has been revealed. TechCrunch does not discuss the script in detail because it could aid cybercriminals in their attacks.

Veteran security reporter Brian Krebs, who previously reported on Operation One-Time Passcode in 2021, said this type of criminal operation shows why you should “never provide information in response to an unsolicited call.” He said that it will become clear.

“It doesn't matter who claims to be calling you. If you didn't initiate the contact, hang up. If you didn't initiate the contact, hang up,” Krebs said. is writing. That advice still applies.

But while services that offer the use of one-time passcodes offer users better security than those that don't, cybercriminals are able to circumvent these defenses, including those that don't. It shows that exchanges and carriers are doing more. do.

Unit 221B's Mr. Nixon said companies are in a “forever war” against bad actors trying to exploit their networks, and said authorities should step up efforts to crack down on these services.

“What's missing is that we need law enforcement to arrest these nuisance criminals,” Nixon said. “Young people are purposefully exploiting this to build their careers, convincing themselves that they are 'just a platform' promoted by their projects and 'not responsible for the crime.' .”

“They want to make easy money in a fraudulent economy. There are influencers who promote unethical ways to make money online. Law enforcement needs to stop this.”