The Indian government is expanding anti-theft and cybersecurity efforts to include both new and used smartphones, a move aimed at curbing device theft and online fraud, but the move also raises new privacy concerns.

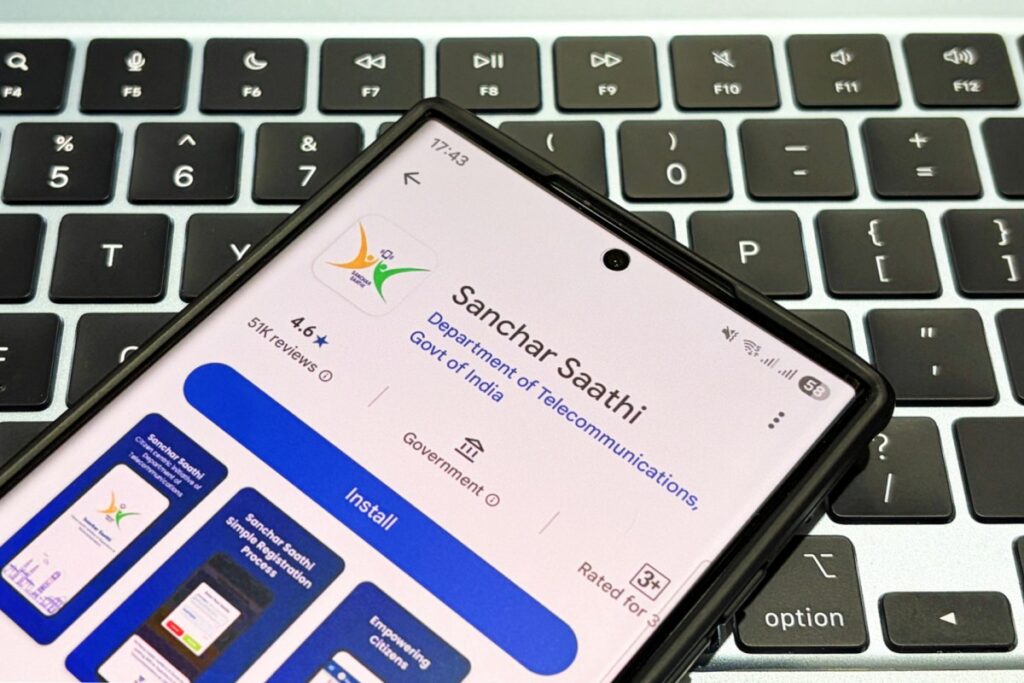

As part of this expansion, India's Ministry of Telecommunications has made it mandatory for businesses buying or trading used mobile phones to verify all devices through a central database of IMEI numbers. This comes in addition to a recent directive directing smartphone manufacturers to pre-install the government's Sanchar Saathi app on all new handsets and push it to existing devices through software updates.

Reuters first reported the news on Monday, and the ministry later confirmed it in an official statement.

Launched in 2023, the Sanchar Saathi portal will allow users to block or track lost or stolen mobile phones. The system blocked more than 4.2 million devices and tracked an additional 2.6 million devices, according to government data. The system was expanded earlier this year with the release of a dedicated Sanchar Saathi app in January, which the government says has helped recover more than 700,000 mobile phones, including 50,000 in October alone.

Since then, the Sanchar Saathi app has become widely adopted. The app has been downloaded about 15 million times and had more than 3 million monthly active users in November, an increase of more than 600% since its launch month, according to marketing intelligence firm Sensor Tower. Web traffic to Sanchar Saathi has also skyrocketed, with monthly unique visitors up more than 49% year over year, according to Sensor Tower data shared with TechCrunch.

The government's order to pre-establish Sanchar Saathi has already drawn significant backlash from privacy advocates, civil society groups and opposition parties. Critics argue that the measure extends state visibility to personal devices without proper safeguards in place. However, the Indian government says the mandate is aimed at tackling the rise in cyber crimes such as duplicate IMEIs, device cloning, fraud in the second-hand smartphone market and identity theft.

In response to the controversy, Telecommunications Minister Jyotiraditya M. Scindia on Tuesday said Sanchar Saathi is a “completely autonomous and democratic system” and users can delete the app if they don't want to use it. The directive, which was reviewed by TechCrunch and circulated on social media on Monday, directs manufacturers to ensure that preinstalled apps are “easily visible and accessible to the end user upon initial use or device setup” and that “their functionality is not disabled or restricted,” raising questions about whether the apps are actually truly optional.

tech crunch event

San Francisco | October 13-15, 2026

Deputy Communications Minister Penmasani Chandra Sekhar said in a media interview that the government's working group on the plan includes most major manufacturers, but not Apple.

Alongside the push for the Sanchar Saathi app, the telecom ministry is piloting an application program interface (API) that would allow recommerce and trade-in platforms to upload customer identity and device details directly to the government, two people familiar with the matter told TechCrunch. This move will be an important step towards setting a nationwide smartphone distribution record.

India's used smartphone segment is rapidly expanding as rising prices for new devices and longer replacement cycles prompt more consumers to seek cheaper alternatives. India will become the world's third largest used smartphone market in 2024.

However, 85% of the used phone sector remains unorganized, meaning that most transactions take place through informal channels and brick-and-mortar stores. The government's measures only target formal re-commerce and trade-in platforms, leaving much of the broader used device market outside the scope of the current measures.

While announcing the pre-installation of the app, the Indian government said the move would make it easier to “report suspected misuse of communications resources.” Privacy advocates say the increased data flows could give authorities unprecedented visibility into device ownership, raising concerns about how the information could be used or misused.

“This is a troubling move to begin with,” Prateek Wagle, director of programs and partnerships at the Tech Global Institute, a Toronto-based nonprofit policy institute, told TechCrunch. “Essentially, you're looking at the possibility that every device is 'databased' in some way. And you never know, something that uses that database might be built into that database at a later date.”

The Indian government has not yet provided details on how the data collected will be stored, who will have access to it, and what safeguards will be in place as the system expands. Digital rights groups say the size of India's smartphone base – estimated at around 700 million units – means even administrative changes could have a huge impact and set a precedent for other governments to study and emulate.

“While the purpose behind unified platforms may be protection, mandating a single government-controlled application risks stifling innovation, especially among private companies and startups that have historically driven secure and scalable digital solutions,” said Meghna Bal, director of the Esya Centre, a New Delhi-based technology think tank.

“If governments intend to build such a system, it must be backed by independent audits, strong data governance safeguards, and transparent accountability measures. Otherwise, this model not only puts user privacy at risk, but also deprives the ecosystem of a fair opportunity to contribute and innovate,” Bar said.

The planned API has also raised concerns from recommerce companies that they could be held liable if sensitive customer information is mishandled.

India's Ministry of Telecommunications did not respond to TechCrunch's request for comment.

Waghre pointed out that while the Sanchar Saathi app appears on users' phones, the broader systems it connects to operate largely out of sight. Planned permissions, data flow and backend changes, including API integrations, may be buried in long-term contracts that most people never read, he said. As a result, users may have little understanding of what information is collected, how it is shared, and the scope of the system.

“Cybercrime and device theft cannot be restricted in such a disproportionate and heavy-handed manner,” Wagle said.

“The government is basically saying my app has to be installed on every device that's sold, every existing device, and every device that's resold,” he said.