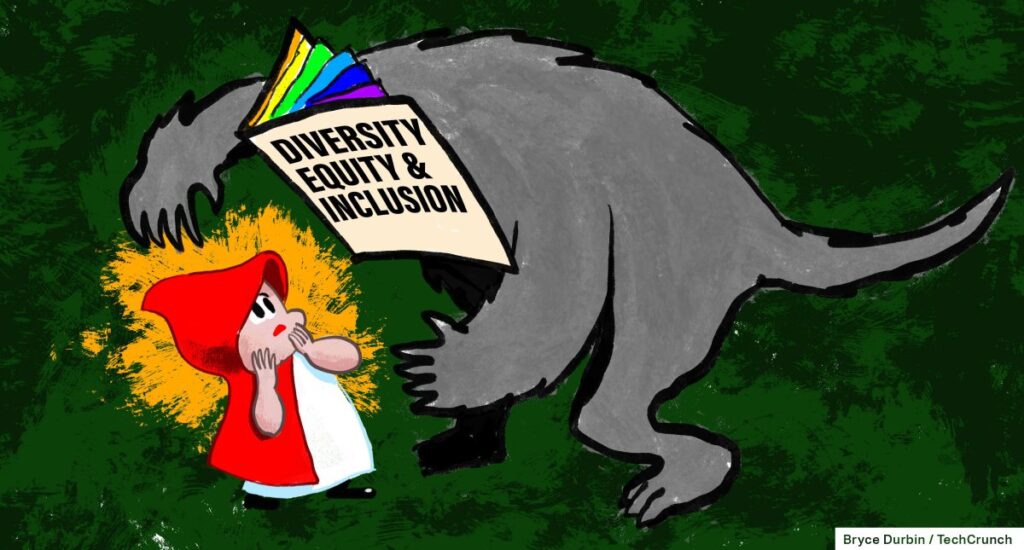

Who's afraid of the Big Bad DEI? The acronym has now become almost toxic. The term creates almost instant tension between those who support it and those who want to abolish it.

A prime example of this divide is the response to a post on X last week by Alexandr Wang, founder of the startup Scale AI, in which he wrote about moving away from DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) and embracing “MEI” (merit, excellence, and intelligence) instead.

“Size is a meritocracy, and we must always maintain that attitude,” Wang wrote. “Inviting someone to join our mission has always meant a lot, and the decision has never been driven by orthodoxy, virtue statements, or what's currently trendy.”

Today, Scale formalized an important hiring policy: we will hire based on MEI (merit, excellence, and intelligence).

This is the email I shared Scale AI team.

———————————————————

Large-scale meritocracy

Since fundraising began, we've been getting a lot of questions…

— Alexander Wang (@alexandr_wang) June 13, 2024

Commenters on X (including Elon Musk, Palmer Luckey, and Brian Armstrong) were thrilled. But LinkedIn's startup community was less enthusiastic. Commenters pointed out that Wang's post makes it seem as though meritocracy is the definitive criterion for finding qualified job candidates, without taking into account that the idea of meritocracy itself is subjective. In the days since the post, more and more people have shared their thoughts and what Wang's comments have revealed about the current state of DEI in the tech industry.

“This post is misguided because those who support the meritocracy argument ignore the structural reasons why some groups are more likely to perform better than others,” Mutare Nkonde, founder of AI policy, told TechCrunch. “We all want the best people for the job, and there's data that proves that diverse teams are more effective.”

Emily Witko, HR director at AI startup Hugging Face, told TechCrunch that the post is “dangerously oversimplified,” but that it garnered a lot of attention on X because it “expresses sentiments that aren't always expressed publicly, and the audience there is eager to attack DEI.” Wang's MEI ideas “make it very easy to refute or criticize any conversation about the importance of acknowledging who is underrepresented in the tech industry,” she continued.

But Wang isn't the only Silicon Valley insider to attack DEI in recent months. He joins the ranks of those who believe that DEI programs implemented at companies over the past few years, which peaked during the Black Lives Matter movement, have caused a setback in corporate profitability and delayed a return to “meritocracy.” Indeed, much of the tech industry has sought to dismantle hiring programs that consider candidates who were often overlooked in the hiring process under previous systems.

In an effort to bring about change, many organizations and leading companies came together in 2020 and committed to placing more emphasis on DEI. This is not simply about hiring people based on the color of their skin, contrary to mainstream discourse, but about ensuring that qualified people from all walks of life are better represented and included in the hiring funnel, regardless of skin color, gender, or ethnic background. It is also about looking at disparities and pipeline issues, and analyzing why certain candidates are consistently overlooked in the hiring process.

According to a report from staffing firm Harnum, the rate of new female hires in the U.S. data industry fell by two-thirds in 2023, to just 12% from 36% in 2022. Meanwhile, the percentage of Black, Indigenous and people of color professionals holding roles of VP of data and above was just 38% in 2022.

Alexander Wang (pictured above) caused a stir on social media when he posted about meritocracy in the tech industry on X. Image credit: Drew Ungerer/Staff/Getty Images

Alexander Wang (pictured above) caused a stir on social media when he posted about meritocracy in the tech industry on X. Image credit: Drew Ungerer/Staff/Getty Images

According to data from job site Indeed, DEI-related job postings are also declining in popularity and are expected to fall 44% by 2023. In the AI industry, more than half of women in a recent Deloitte survey said they had left at least one employer because they were treated differently than men, and 73% said they had considered leaving the tech industry due to pay disparities and difficulties in career advancement.

But Silicon Valley, an industry that prides itself on being data-driven, can’t let go of the idea of meritocracy, despite mountains of data and research showing that it’s merely a belief system and can lead to biased results. The idea of hiring the “best person for the job” without any consideration of human sociology is a pattern-matching method, creating teams and companies made up of similar people. Research has long shown that diverse teams perform better. And it only raises questions about who Silicon Valley considers talented and why.

Experts we spoke to said this subjectivity reveals other problems with Wang's letter, primarily that Wang presents MEI as a revolutionary idea, not one that Silicon Valley and most of corporate America have supported for years. The acronym “MEI” seems a pejorative nod to DEI and is intended to underscore the idea that companies must choose between hiring diverse candidates or those who meet certain “objective” qualifications.

Natalie Sue Johnson, co-founder of DEI consulting firm Paradigm, told TechCrunch that research has found that meritocracy is a contradiction in principle, and that organizations that place too much emphasis on it increase bias. “Meritocracy frees people from the idea that they have to strive to be fair in their decision-making,” she continued. “People think that meritocracy is something you're born with, that it's not something you have to achieve.”

As Nkonde noted, Johnson noted that Wang's approach fails to acknowledge that underrepresented groups face systemic barriers that society is still struggling to address. Ironically, the people who achieve the most may be those who acquire the skills they need for the job despite barriers that impacted their educational background or prevented them from putting the kind of college internship that would impress Silicon Valley on their resume.

Johnson said it's a mistake to treat someone as a faceless, nameless candidate without understanding their unique experience and therefore employability. “There's a nuance there.”

Witko adds: “Because meritocratic systems are built on standards that reflect the status quo, they perpetuate existing inequalities by continuing to favor those who are already advantaged.”

Given how vitriolic the term DEI has become, giving Wang some leeway and developing a new term that still conveys the value of fairness for all candidates, even if “meritocracy” is wrong, wouldn't be a bad idea. And Wang's post suggests that Scale AI's values may be aligned with an ethos of diversity, equity and inclusion, even if Wang doesn't realize it, Johnson said.

“Searching for a broad range of talent and making objective hiring decisions that don't penalize candidates based on their identity is exactly what diversity, equity and inclusion efforts are about,” she explained.

But again, Wang undermines this point by endorsing the false belief that meritocracy produces outcomes based solely on individual ability and merit.

Maybe it's all a contradiction: Scale AI's treatment of its data annotators, many of whom live in third-world countries and scrape by on shoestring wages, suggests the company has little interest in challenging the status quo.

Scale AI's annotators work on tasks over multiple days in eight-hour workdays with no breaks and are paid a minimum of $10 (per the Verge and NY Mag). It's thanks to these annotators that Scale AI has built a business worth over $13 billion and has over $1.6 billion in cash in the bank.

When asked to comment on the allegations made in the Verge and NY Mag articles, a spokesperson pointed to this blog post, which describes the work of the company's human annotators as “gig work.” The spokesperson did not respond to TechCrunch's request for clarification on Scale AI's MEI policy.

Johnson said Wang's post was a good example of a trap that many leaders and companies fall into.

She wondered whether we could believe that having a meritocratic ideal was enough to lead to truly meritocratic outcomes and promote diversity.

“Or do we recognize that ideals alone are not enough, and that intention is required to truly build a more diverse workforce where everyone has equal access to opportunity and can do their best work?”