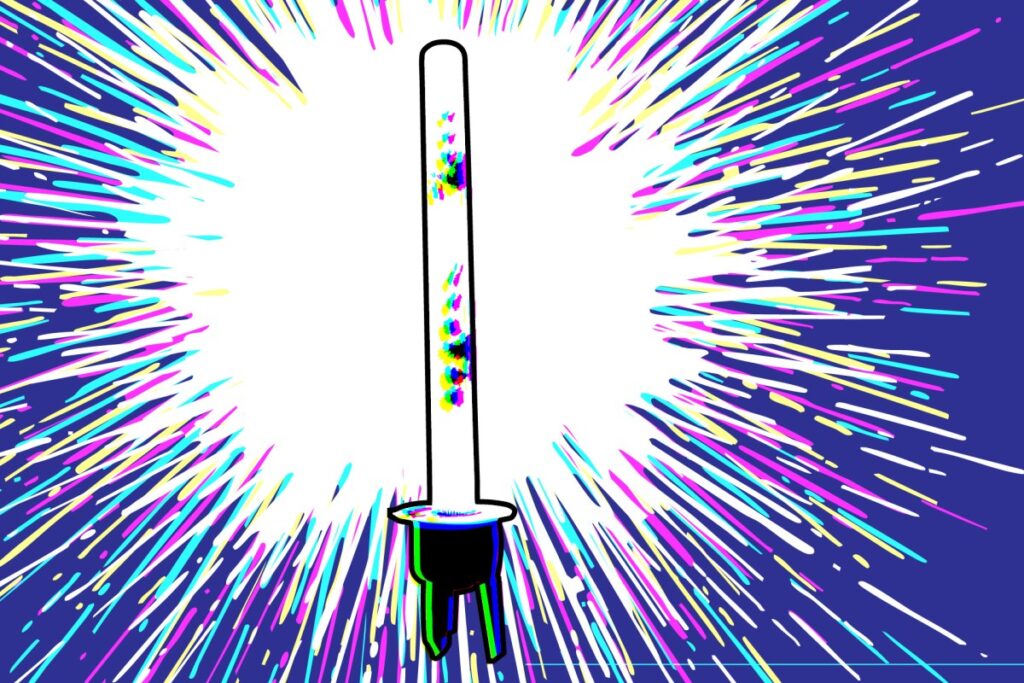

If there's one thing that's come from the worlds promised to us in Back to the Future, The Jetsons, or countless other sci-fi series, it's Spiralwave co-founder and CEO. Abed Buhari showed me this in a video. phone. Waves of purplish-white plasma rose and fell rhythmically within the metal-shielded column, igniting to the metronome-like clicks emanating from elsewhere in the chemistry kit.

This is not a space propulsion system, but a device that can capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or smoke stacks and convert it into something useful. “You can see the plasma being generated here in very fast pulses,” Buhari told me. “Every time you pulse, it breaks down CO2.”

The plasma wave is ignited by three different microwave pulses with unique frequencies that target different molecular bonds, causing a series of chemical reactions.

“The first splits CO2 into CO, the second splits H2O into H and OH, and the third combines them into methanol,” Buhari said. SpiralWave pitched its technology on the Startup Battlefield stage at TechCrunch Disrupt 2024.

Image credit: SpiralWave

Image credit: SpiralWave

Methanol is a simple hydrocarbon made up of just a handful of atoms, but that simplicity gives it flexibility. It can be burned directly in an internal combustion engine, as in some modern race cars, or it can be refined into more complex hydrocarbons, such as jet fuel. It can also be used to manufacture chemicals used in various industries.

Depending on the carbon dioxide concentration, SpiralWave's process converts 75 to 90 percent of the system's electrical energy into chemical energy that is stored in the form of methanol. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are at the lower end of the range, and industrial exhaust gases are at the upper end. This compares favorably with other methods of producing methanol from captured CO2, which are approximately 50% efficient.

Buhari arrived at carbon removal in a roundabout way. His previous startup, KomraVision, made spectrometers, and he built some of his own semiconductor manufacturing equipment to build specialized components. Some of these tools used cold plasma, a type of energized substance commonly found in fluorescent lights. “At that time I was very deep in cold plasma,” he said.

But with the climate crisis looming, “we needed to build something that could stop the biggest challenge on Earth these days, which is removing massive amounts of carbon dioxide,” he said.

Buhari had a cold plasma hammer, but carbon pollution was a lot like a nail.

After building a small prototype to prove the concept, he met co-founder Adam Amed, then a student at Santa Clara University, and the two founded Spiral Wave. Mr. Amed is currently based in Silicon Valley and leads business development, while Mr. Bukhari is based in Austria, about 30 minutes from Munich, where he leads research and development. Amed said the company has raised $1 million from IndieBio.

SpiralWave's initial prototypes range from knee-high nanobeams to microbeams about 2 meters or 6.5 feet long. The device can produce one ton of methanol using a 90% carbon dioxide stream and 7,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity. A more dilute stream (about 9%) takes 8,500 kilowatt-hours and ambient air takes 10,000 kilowatt-hours. All of these compare favorably with other sources of e-methanol today.

The team also has plans for larger devices called MegaBeam and GigaBeam. The latter will be 100 meters high and will be able to remove 1 gigaton of CO2 per year. “To fight climate change, we need to remove 10 gigatonnes of CO2 a year,” Buhari said.

In the meantime, SpiralWave is focused on replicating its small devices and placing them in shipping containers placed at customer sites. The two are optimistic about their prospects. “Ten 20-foot containers would create the largest electronic methanol plant ever,” Amed said.